Nature Conservancy Works To Restore Oklahoma's Blue River

The Nature Conservancy is working to restore Oklahoma's Blue River by planting thousands of native trees nearby.Wednesday, September 21st 2022, 10:15 pm

DURANT, Okla. -

The Nature Conservancy is working to restore Oklahoma's Blue River by planting thousands of native trees nearby.

The work, which has roots in Tulsa, is part of a greater effort to protect the river for future generations.

The Blue River flows for more than 140 miles through southern Oklahoma. It supports more than 80 different species of fish. Other wildlife, and people depend on it, too.

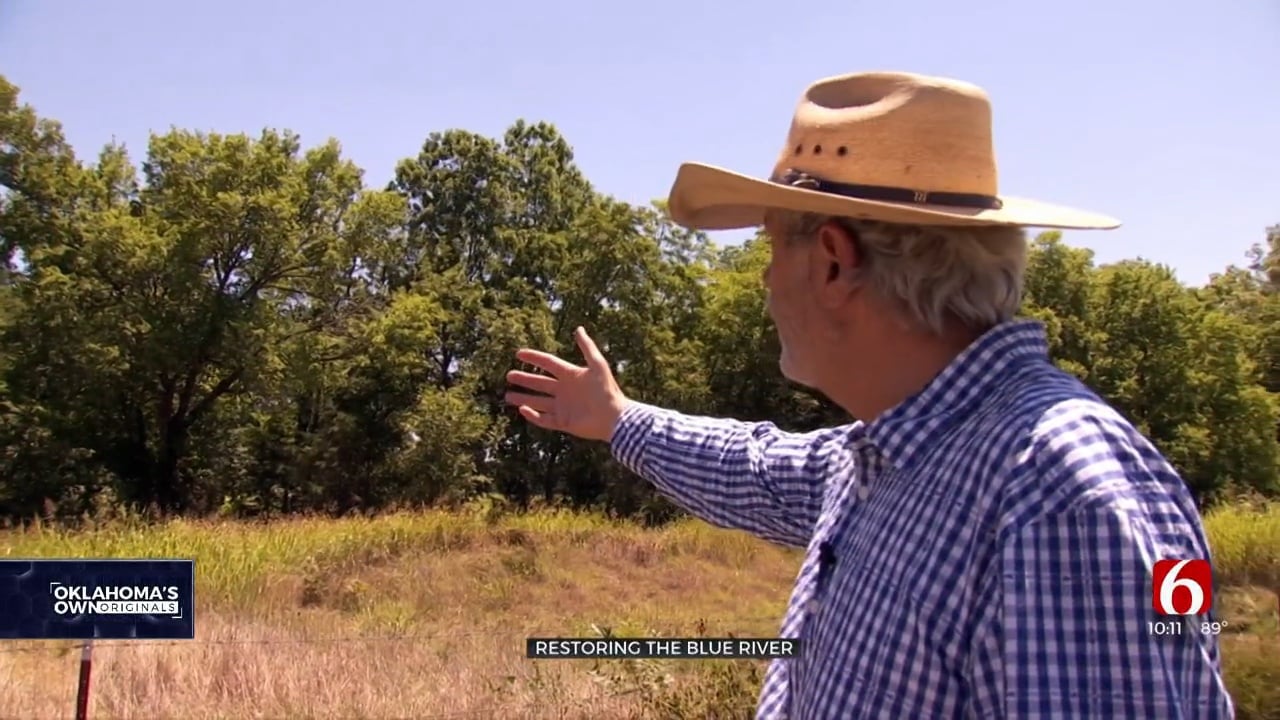

And it's part of John Moody's backyard. The land has been in his family for four generations.

"We're very proud stewards of this little piece of what we think is paradise here on the Blue River,” Moody said.

That paradise needs protecting, says The Nature Conservancy, Chickasaw Nation, and other partners. Together they are working to "restore" the river.

"It's actually a very high-quality river. But we just don't want to see it get degraded or in poor quality,” Jeanine Lackey with The Nature Conservancy said. She is the project director for the Arbuckle Plains and Blue River.

"Right now, the upper portion of the Blue is not in trouble, but let's not wait until it is in trouble,” Chickasaw Nation Director of Natural Resources Kris Patton said.

Over the last 200 years, The Nature Conservancy said native trees were cut down and the land around the river was transformed into hay meadows, opening the door to problems like erosion.

Now The Nature Conservancy is taking steps to breathe new life into the river, by turning to historic roots in the ground.

TNC planted 4,001 trees in 2020 along a small part of the river. This was the trees' second summer in the ground.

The Nature Conservancy was strategic about what to plant. Scientists and volunteers put 14 different kinds of trees and shrubs in the ground. All of the plants came from Southwood's in Tulsa.

The nursery grew the seedlings and shrubs based on a plant list from TNC and the Oklahoma Biological Survey, showing what would have been native to the land.

Lackey and TNC Watershed Health Director Kim Elkin are waiting for Cottonwood, Oak, Pecan trees, and others to grow.

"Eventually they'll grow up to be really large trees,” Lackey said. “And all those roots help keep that soil in place. And that just helps us restore that system to the way it used to be historically."

And that, scientists said, will eventually have an impact downstream. The City of Durant depends on the Blue River for all of its water. So does the Choctaw Nation. The Nature Conservancy expects the work it’s doing now to save the city money because the water won't need as much treatment.

But the reality is that it will take decades to see the impact.

"It's just going to take a long time,” Lackey said. “But that's the business we're in, you know? We're restoring ecosystems that took decades to get degraded. And it's going to take decades to become resilient."

The Nature Conservancy is doing this work where it can, along one mile of the Blue River it owns. But most of the land along the river is owned by private landowners.

"As you see the Blue today, it's not as blue as it normally is. It's got a little bit of a sediment load in it, from recent rains. And so it tells us we still have work to do here. There's work to be accomplished with landowners,” Patton said.

Patton works with landowners directly to help them manage their land.

"It's not a regulatory function. We're not telling the landowners what to do,” he said. “We're just saying if there's a practice, a best management practice that you want to implement, we're going to work with you through this group to figure out how to get that funded."

Patton points to Moody as an example of someone leading the way.

"I think the balance that ranchers, landowners, (and) land stewards have to face is the expense of something as aggressive as planting trees. Not everybody can afford to do that,” Moody said.

One thing he's doing is actually removing some trees from his property: the invasive Eastern Redcedar.

"There's nothing growing here; it's all cedar leaves that have died,” Moody said while pointing to the ground on part of his property.

"Removing this and restoring it gives you more grazable acres and it also improves the habitat within the riparian area," said Patton.

"That's exactly right," said Moody.

Moody showed News On 6 part of his property where he had cedars removed. The difference in the land is obvious: it's lush and green, instead of barren.

It is just one example of what Moody is doing to improve this ecosystem because The Nature Conservancy can't do it alone.

"I'm hoping my granddaughters look at it the same way and take care with it when it becomes their turn to make decisions,” Moody said.

The Nature Conservancy said the reason it is able to do this $3 million restoration project is because of the Oklahoma Department of Transportation.

Federal legislation, including the Clean Water Act, requires transportation departments to restore wetlands and streams if any permanent impacts were made by construction work from roads and bridges.

More Like This

September 21st, 2022

November 10th, 2022

November 9th, 2022

Top Headlines

December 14th, 2024

December 14th, 2024

December 14th, 2024